Sanctions are often described as blunt instruments, but that’s only half the story. If you look closely, you’ll see a web of economic restrictions quietly redrawing the lines of international trade and diplomacy. Five different regimes—Iran, Russia, Venezuela, North Korea, and Myanmar—stand as real-world case studies for how these measures ripple far beyond their intended targets.

Have you ever wondered what happens when a country is cut off from selling its most valuable resource? Iran’s energy sector sanctions did just that. In theory, blocking Iranian oil exports and limiting its access to global banking should have squeezed Tehran into changing course. Yet, the effect has unfolded on multiple fronts. Not only did Iran look for new buyers, but it also helped foster a shadow market for crude oil. Countries less concerned about Western approval—think China or some smaller Asian economies—began to buy oil at a discount, indirectly propping up Iran’s revenues. Meanwhile, energy traders in neighboring countries found creative workarounds. Secondary sanctions loomed large here, threatening any foreign bank or firm that dared to facilitate deals outside the official channels. This threat often scared off European and Japanese players—leaving the field open for risk-tolerant brokers.

As Albert Einstein once reflected, “In the middle of difficulty lies opportunity.” Sanctioned states have taken that to heart, out of necessity. Iran pushed ahead with alternative payment systems, barter deals, and even cryptocurrency adoption, aiming to sidestep the US dollar whenever possible. But the story isn’t just about economic survival. The spillover effect has forced global commodity supply chains to reorient. Indian refineries, for instance, sometimes take in Iranian crude passed off as another blend, while European refiners hunt for new suppliers, nudging up prices worldwide.

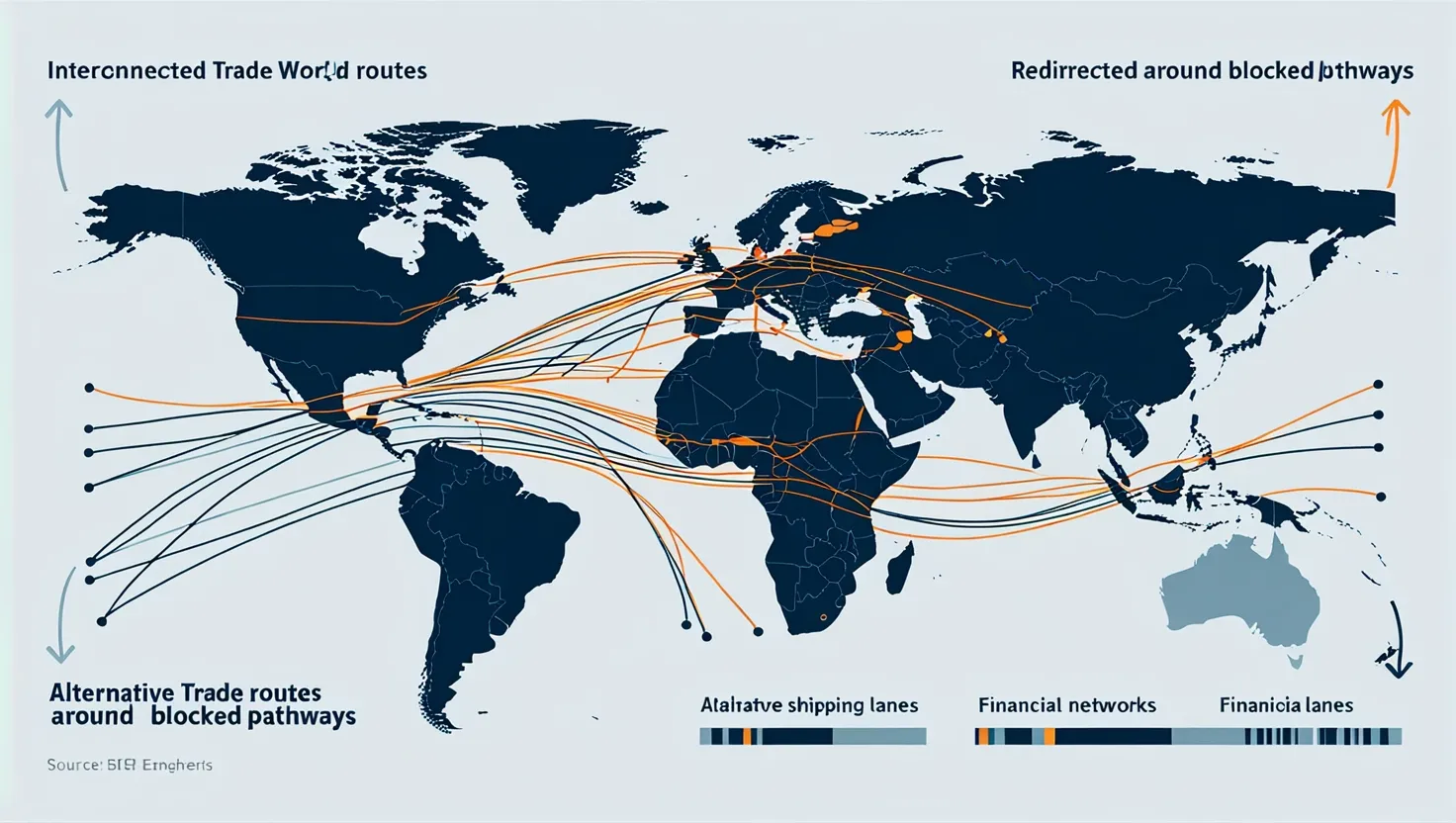

Now let’s turn to Russia’s situation after the Ukraine invasion. Watching an economy the size of Russia’s face sweeping export bans, asset freezes, and the SWIFT banking cutoff sounded, at first, like an economic death sentence. But the reality has been much messier. Did you expect networks of traders in Turkey, the Middle East, and China to step in and funnel critical goods to Russia? That’s what happened. The black-market trade boomed, and enforcement agencies in the West began to play a never-ending game of cat and mouse. Ongoing debates about the actual effectiveness of these restrictions have intensified. Some analysts claim that Russian military production has slowed, yet others point out that the country found surprising reserves of economic resilience by rerouting trade through third countries.

You might ask: with so many rules in place, what about everyday people? Here’s the paradox. Even with humanitarian exemptions written into nearly every major sanction regime, getting aid in and money out remains a bureaucratic maze. Bankers and shipping firms, worried about falling afoul of broad restrictions, often shy away from transactions that are technically legal. This “chilling effect” probably wasn’t what legislators had in mind. As a result, medicines and food sometimes sit in warehouses, delayed by compliance checks that stretch on for weeks.

Consider Venezuela, where oil and financial sanctions struck at the country’s economic heart. Years of falling revenue and blocked access to global capital markets have hit the average citizen harder than the regime’s elite. The government, seeking new sources of foreign exchange, has struck barter deals with countries hungry for cheap oil. You might be surprised to learn that some Caribbean islands have relied on these gray-market flows to keep their lights on. Meanwhile, debt restructuring talks—usually a lifeline for troubled economies—have become almost impossible for Venezuela. The country sits in a kind of financial limbo, unable to issue new bonds or access traditional lenders.

North Korea provides perhaps the most clear-cut example of broad international isolation. It faces near-total trade embargoes in an attempt to curb weapons development. Yet, satellite images and customs data reveal mysterious ships transferring cargo at sea, or rerouted through obscure Chinese ports. Sometimes, the measures meant to isolate a regime have the perverse effect of making its economy even harder to track. Pyongyang has also become a pioneer in cyber theft, generating millions in hard currency through sophisticated hacking schemes—the digital world, after all, knows few borders.

One of the more recent examples is Myanmar. After the military coup, targeted financial sanctions aimed at the junta’s leadership tried to squeeze the regime without punishing the broader population. The challenge? Much of Myanmar’s economy is run through networks that are difficult to monitor or control from the outside. The regime quickly found new routes to access capital, and local businesses grew adept at working around formal restrictions. International banks, wary of reputational risk, began pulling back, inadvertently making it even harder for civil society organizations to operate or for humanitarian projects to continue.

Let’s pause and ask: are these sanctions making the world safer or fairer? Opinions diverge sharply. Diplomatic leaders insist they’re a vital tool—what’s the alternative, military action? Critics counter that the track record is mixed. The intended targets often entrench their positions, while ordinary people pay a hidden price in higher food costs, inflation, and lost economic opportunity. Did you know, for instance, that global food prices spiked after Russia’s sanctions distorted grain and fertilizer flows? Or that new shipping patterns—often less efficient—mean extra costs at every stage?

Secondary sanctions are another force multiplier, often ignored in headline coverage. These measures threaten to punish companies even in countries not formally participating in the primary boycott, if they help sanctioned regimes. It’s a way of globalizing restrictions, but it also risks fracturing alliances. Smaller states or corporations may choose strategic neutrality, quietly continuing business as usual and hoping not to attract attention.

Here’s a quote from Winston Churchill that seems apt:

“However beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results.”

What about new ways around the restrictions? The past five years have seen a surge in alternative payment systems, especially when major players are shut out of international banking. Russia and China have accelerated the rollout of non-SWIFT messaging tools to transfer money. Cryptocurrencies are playing a bigger role than many realize, both in facilitating legal trade and in helping sanctioned actors move funds across borders without detection. There’s a new scramble to digitize trade documentation, insurance, and letters of credit—all moves that chip away at older systems shaped by Western banks.

Sometimes, these responses forge unlikely alliances. Countries targeted by sanctions often band together, sharing know-how, setting up backchannel trade networks, and swapping commodities—oil for rice, wheat for technology parts. This may seem like a small-scale workaround, but over time, it nudges global trade away from familiar patterns. We should ask ourselves: if sanctions create new winners and losers, who ultimately benefits from the new world order?

Sanctions also spark innovation—not just in commerce, but in diplomacy. States that once played minor roles in trade now act as intermediaries, brokers, and connectors. Places like Turkey or the UAE have become logistics hubs, where goods are repackaged and relabeled to sidestep restrictions. While this redirection adds cost and complexity, it also creates new economic opportunities for states willing to walk a diplomatic tightrope.

Another lesser-discussed aspect is the impact on global legal and compliance industries. The demand for sanctions compliance officers has ballooned. Law firms and consultancies race to interpret shifting regulations and design systems to flag suspicious transactions. “Sanctions busting” has become big business, with some firms specializing in finding the loopholes and others in closing them.

Sometimes, sanctions regimes prompt countries to invest heavily in domestic industries, spurring localized manufacturing and new economic sectors. Russia’s renewed focus on self-sufficiency, after its exclusion from Western suppliers, is a telling example. While some sectors have suffered from the loss of high-tech imports, others—like agriculture—have thrived thanks to a captive market.

Let’s reflect for a moment: How do these evolving systems affect the balance of power? When nations barred from traditional trade routes find new ways to cooperate, it shifts the locus of influence from Washington, Brussels, or London to Ankara, Dubai, and Shanghai. The world becomes less predictable, and perhaps less controllable, as economic power diffuses across new networks.

Reflecting on history, consider John F. Kennedy’s words:

“Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.”

The humanitarian dimension cannot be overlooked. Efforts to add exceptions for food, medicine, and basic services often stumble over bureaucratic hurdles. Well-meaning exemptions get buried under paperwork, as banks and insurance firms take an ultra-cautious stance. The result? Aid organizations sometimes see donations stuck in limbo, and vital goods go undelivered to those who need them most.

One of the most intriguing questions is whether sanctions achieve their stated policy goals. There are cases of incremental movement—Iran did enter nuclear negotiations, Myanmar faces sustained military pressure—but the causality is rarely clear. Regimes often double down on repression or look inward, building narratives of resistance that bolster their legitimacy.

You might be asking: is there a better way? That’s the debate now at the heart of international relations. Some call for more targeted measures, smarter enforcement, and easier humanitarian access. Others argue for fresh diplomatic strategies, suggesting that sanctions be paired with concrete incentives and clear paths for removal.

In my view, the real story of sanctions is one of adaptation. For every new measure imposed, there’s an equally creative response from those affected. The world’s economic map is not fixed—it shifts and morphs in response to these pressures. As new alliances and trade routes are forged in the shadows of restriction, the future of diplomacy and commerce may look very different from the familiar models of the past.

So next time you read about a new round of sanctions, ask yourself: Who stands to gain? Who will find a way around? And what unseen threads are now drawing countries together, beneath the surface of international headlines? The answers, as always, lie not just in boardrooms or parliaments, but in the lived experiences of millions whose daily lives shift with each new regulation and workaround.