Every day, leaders find themselves standing in the fog of gray space—a place where the rules aren’t clear, the data isn’t complete, and traditional guidelines start to collapse. It’s a space I know well, and one that demand a particular kind of leadership: calm amid uncertainty, decisiveness without arrogance, and the humility to know we rarely have the full picture before acting.

“Leadership and learning are indispensable to each other.” – John F. Kennedy

Let’s talk first about getting comfortable with ambiguity. For years, I thought the goal was to eliminate uncertainty. I’d dig for more data, seek another expert opinion, delay decisions in the hope that clarity was just around the corner. But the truth: clarity rarely arrives gift-wrapped. Most pivotal choices are made without having all the pieces. Steve Jobs, making the iPhone, didn’t wait for absolute consensus. Angela Merkel, guiding Germany through the Eurozone crisis, had to move forward while the facts were still forming. With practice, I’ve learned to say out loud, “Here’s what we know—and what we don’t.” The phrase is liberating. When you name uncertainty, it loses some of its power over you. Have you ever noticed how admitting you don’t have a perfect answer makes it easier for others to support you?

“If you wait for perfect conditions, you’ll never get anything done.” – Ecclesiastes

Next comes the question of frameworks. If ambiguity is a given, how do I avoid chaos? Here’s where clear decision-making structures come in. I outline acceptable risk beforehand. For example, early in Amazon’s history, Jeff Bezos encouraged “two-way door” decisions—choices that could be reversed—versus “one-way doors,” which locked you in. Most decisions, he explained, are two-way. A structured framework lets us act boldly in uncertainty because we know the boundaries. I’ve borrowed from this idea and spell out with my teams: What are we willing to risk? What’s our fallback if things don’t pan out? Setting limits not only prevents reckless moves, but also provides psychological cover that encourages innovation.

“What is not started today is never finished tomorrow.” – Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

But structure is only effective if people feel safe. When I’m wrestling with ambiguity, I need my teams to surface doubts, minority opinions, and crazy alternatives—without worrying if they’ll be punished for it. Psychological safety has become a buzzword, yet at its heart it asks: Do people believe it’s okay to say, “I’m not sure, but here’s an idea”? Pixar’s Ed Catmull built this into filmmaking with “braintrust” meetings, where radical candor was invited and mistakes were seen as pathways to better storytelling. Creating this environment isn’t about being nice—it’s about generating enough candor that the very best ideas can rise to the surface. If my team is just echoing my thinking, I know I’m in trouble. When was the last time someone disagreed with you openly?

“In the confrontation between the stream and the rock, the stream always wins—not through strength but by perseverance.” – H. Jackson Brown Jr.

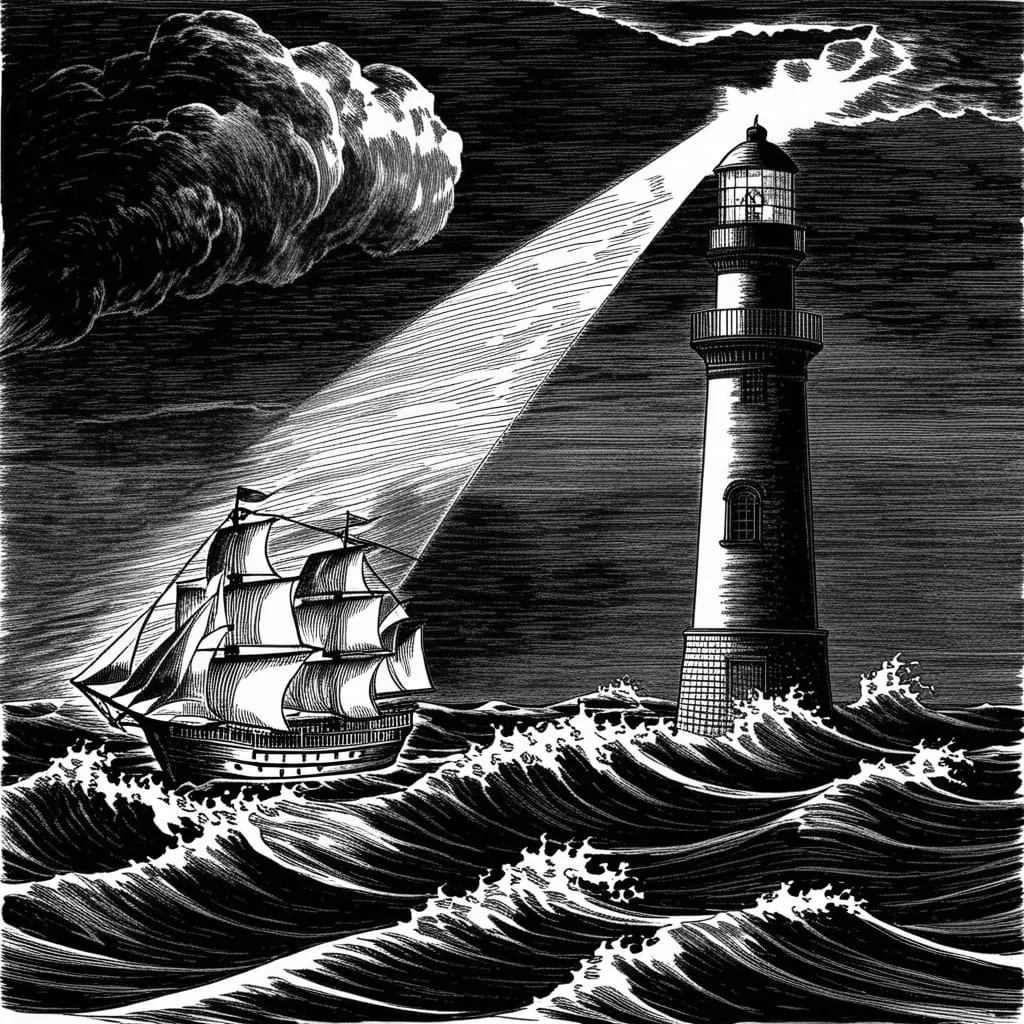

I’ve learned to avoid the trap of false finality. In gray space, change isn’t only possible; it’s probable. That’s why staged or phased decisions become essential. Imagine a ship caught in thick fog: you don’t set the course once and sail blindly—you check your bearings again and again, adjusting as new landmarks emerge. In the corporate world, Satya Nadella’s approach at Microsoft stood out. Transforming a massive organization, he implemented pilot programs and incremental tests, then scaled what worked. It’s a lesson: making smaller, reversible moves provides room to course-correct. This reduces fear for everyone involved. Have you tried splitting a problem into smaller bets, rather than committing everything in one go?

“He who deliberates fully before taking a step will spend his entire life on one leg.” – Chinese Proverb

One part often skipped is documentation. Early in my career, I’d make the call, move forward, and only later wondered: why did we pick that path? Now, I take time to explicitly state the assumptions—and the rationale—behind each decision. It’s not just for legal or audit purposes. It allows everyone to revisit our thinking when facts change. In one organization, we faced a fast-moving supply chain disruption and decided to double our supplier base. That choice, and the reasoning behind it, was detailed for the team. Months later, with the crisis over, those notes became invaluable when we had to explain our expenditures—and when we considered whether to keep the new model. Learning from history means keeping a history to learn from.

“History is a vast early warning system.” – Norman Cousins

Venturing deeper, I’ve seen some unexpected truths. The most confident-seeming leaders aren’t always the bravest; sometimes, they’re just masking fear of being wrong. The greatest courage, I think, is honestly saying, “I don’t know—let’s find out together.” It’s a posture of intellectual humility that doesn’t paralyze action, but tempers it with inquiry. That humility is the shield against the danger of overconfidence during disruptive market shifts. Think of Nokia’s collapse or Kodak’s fall: both failed not because they lacked top talent, but because their leaders clung too tightly to the certainty of old successes.

“Success is not to be pursued; it is to be attracted by the person you become.” – Jim Rohn

When the playbook falls short, I look to lessons from unlikely places. In the Navy, submarine captains are taught to “call the maneuver” out loud before acting—so even in high-pressure moments, assumptions get checked in real time. This practice has found its way into some boardrooms I’ve visited: leaders articulate what they’re about to do and why, inviting others to stop and ask questions before the course is set. Does your team have a way to pause before big steps, or does everyone rush forward hoping for the best?

Throughout history, markets have shifted overnight and organizations have had to rewrite themselves in the ruins of their former sureties. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, airlines rewrote schedules, manufacturers pivoted to make ventilators, and restaurateurs turned to online delivery with barely a moment’s notice. The leaders who fared best rarely had all the data; instead, they relied on trust—trust in their teams, their processes, and an ongoing willingness to adapt as reality shifted under their feet.

“Trust, but verify.” – Ronald Reagan

Part of building that trust involves shaping team confidence. I constantly ask: how can I help my people feel empowered when none of us knows the exact path? I’ve found that what works isn’t false bravado—it’s showing them we can handle whatever comes next together by preparing openly for unexpected turns. When mistakes happen (and they do), I model learning, not blame. When we guess right, I highlight the collective wisdom. Confidence, it turns out, comes less from certainty and more from surviving the uncertain—together.

Sometimes I ask myself: Would I rather make the right decision, or create an environment where the next right decision is more likely? It’s a humbling question. In gray space, leadership is often about teeing up the future—not solving for every variable today, but keeping momentum alive and the team steady enough to adjust at each new fork in the road.

And when the dust settles, after the crisis or the disruption, I review not just the outcomes but the process. Were we clear about what we knew and didn’t? Did we treat frameworks as living guidance, not rigid rules? Did my team feel safe and actually speak up when they had doubts? Did we revise as we went, or cling to our first answer? Did we capture our logic so we could learn, or did we just plow ahead and hope for the best?

If you lead, you’ll meet “the gray” over and over. Some see it as a hurdle. I see it as a calling—a test not only of decision-making, but of character, patience, and humility. Each time, I remind myself and my team: our goal isn’t safety in certainty, but progress in complexity. The gray space might never disappear, but we can move through it—deliberate, aware, and very much together.

“There are no secrets to success. It is the result of preparation, hard work, and learning from failure.” – Colin Powell

So I invite you next time you face the ambiguous and the messy to pause and ask: What do we really know? What does safety look like for my team? Can we sketch a path that lets us change course if we need? Are we capturing what we learn as we go? Most of all: Am I willing to stay curious, adaptable, and open—especially when everyone is looking for quick answers?

The gray space won’t ever be easy. But, as leaders, moving forward—calmly, openly, and together—is the work we’re called to do.